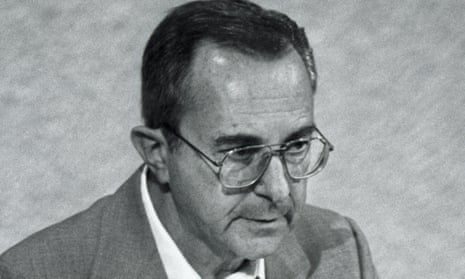

Over the course of Israel’s first seven decades Moshe Arens, who has died aged 93, served his country as defence minister three times, as foreign minister and through his brilliance as an aeronautical engineer. He was an early mentor of Benjamin Netanyahu, though promoted him so successfully that Arens’ own hopes of becoming prime minister evaporated in the process.

While he held the defence portfolio during the 1991 Gulf war, he wanted to retaliate when Iraqi Scud missiles hit Tel Aviv. But President George HW Bush warned that such action would sabotage the anti-Saddam coalition.

Four years later Arens wrote in his book Broken Covenant: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis Between the US and Israel that the Bush administration had tried to “bring down the democratically elected government of Israel”. He felt bitter because he had lived and worked in the US, and married his wife, Muriel Eisenberg, there. Memories of the Holocaust also coloured his views.

Born in Kaunas, Lithuania, and brought up in Latvia, Moshe was the son of a dentist mother and businessman father. In 1939 his family left for the US, settling in New York.

A leader in Betar, a rightist Zionist youth movement, Arens believed in Jewish self-reliance and an “iron wall” against Arab nationalism. He graduated in mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1947, after two years service in the US Army, and moved to Israel when it came into being in 1948.

He fought for Menachem Begin’s Irgun underground and helped found Herut, a precursor to the rightwing party Likud. Soon Betar posted him to Europe and North Africa to teach Jewish communities self-defence. Decades later, Maghrebi Jews came to Israel en masse and in 1977 their support helped Likud defeat Labour for the first time.

Arens designed water systems for Tel Aviv before studying aeronautical engineering at the California Institute of Technology (1951-54) and working for American aviation firms. Back in Israel, he became associate professor at the Haifa Technion (1957-62), vice-president of Israel Aircraft Industries (1962-71), and manager of the Cybernetics Company (1972-77). He won the Israel Defence prize in 1971 for developing aircraft including the Aravah cargo plane and the Kfir fighter.

In 1973 he was elected to the Knesset, chaired its foreign affairs committee (1977-82) and was ambassador to Washington (1982-83) during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. While there, he appointed Netanyahu, at the time a furniture salesman, his deputy.

After Ariel Sharon resigned as defence minister in 1983, following censure for massacres at the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps, Arens returned to Jerusalem to succeed him.

He soon revealed a pragmatic side. Earlier he had opposed returning the northern Sinai to Egypt; now he withdrew Israeli troops to southern Lebanon. In 1984 he became minister without portfolio, two years later gaining responsibility for Israel’s Arab minority and championing their right to equal status. He left government in 1987 when colleagues rejected his brainchild project, the indigenous Lavi fighter jet.

The intifada was a year old when Arens replaced Shimon Peres as foreign minister in December 1988, with Netanyahu again his deputy. He proposed local Palestinian elections to stem unrest, but barred the PLO, whom he blamed for “the worst horrors since the second world war”. He also rejected ceding territory, arguing that Israel needed “secure borders in this most dangerous part of the world”. Yet behind the scenes Arens agreed that East Jerusalem Arabs and Palestinian deportees could negotiate with Israel.

Yitzhak Shamir, the prime minister, reappointed Arens defence minister in June 1990. One month later Arens warned US officials of Iraq’s impending attack on Kuwait, but was rebuffed. He surprised fellow conservatives by condemning West Bank settler vigilantes, and helped facilitate the Madrid peace conference of October 1991, though complained that Washington favoured only “compliant” Israeli politicians.

Labour won power in 1992, leading Arens to accuse the defeated Shamir of placing settlers’ interests above those of ordinary Israelis. Having turned down an offer to replace Shamir as Likud leader, in 1993 Arens backed Netanyahu, who was elected prime minister in 1996. In 1999, however, the 73-year-old charged his protege with mismanagement and challenged his leadership. Netanyahu easily beat Arens in party primaries, and then made him defence minister. That did not last long, as Likud lost elections in May 1999.

In February 2001 Arens was recalled to “sell” new prime minister Sharon to a wary Washington. Four months later he criticised Sharon’s “restraint” as the al-Aqsa intifada escalated. Arens stayed loyal to Likud when Sharon left the polarised party in 2005.

Arens had already retired from the Knesset in 2003 – not that he stopped working. In 2011 he published Flags Over the Warsaw Ghetto in English and Polish, about the “untold story” of Betar-affiliated fighters in the 1943 uprising.

In 2018 he released his political memoir, In Defence of Israel. And his regular Haaretz columns showed a mind that blended principled liberalism with ultra-nationalism.

He decried Israel’s 1993 Oslo agreement with the PLO as a monumental error born of impatience. On the other hand, he fiercely opposed Netanyahu’s 2018 nation-state law as needless, damaging and demeaning to the Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Warm and courteous in private, Arens seemed too patrician to be a populist leader. After his death Uri Zaki, founder of a leftist pro-democracy NGO, spoke of Arens’ adherence to “ideological debate with decency”.

He is survived by Muriel, his sons, Yigal and Raanan, and daughters, Aliza and Rut.