I entered through a discreet door in Whitehall, that of the Cabinet Office, and passed down a long sequence of spaces – literally, corridors of power – that run parallel to Downing Street, a few metres to the left. I continued to the point where another door or two would, were I so authorised, have got me into No 10. I was admitted to the office of Peter Mandelson, minister without portfolio, at this time in 1998 the second most powerful man in government, sometimes called the Prince of Darkness.

I didn’t know what to expect. Jonathan Glancey, then architecture and design editor of the Guardian, had been yelled at and threatened by a government press officer for his attacks on the Millennium Dome. I had written a front-page story for the Evening Standard, whose message – “New threats to the dome” – had graced newsstands all over London. It turned out I was getting the “good cop”. Mandy (as he was also tagged), reclining informally on one of the leather couches in his office, told me how terribly disappointed he was in my criticisms, as he particularly admired my writing.

He complimented me on my shirt. We discussed its designer, Paul Smith, and the shop he had just opened in Notting Hill. He asked artful questions that seemed designed to extract the identity of my sources. And that was about it. But it was an unusually high degree of interest, in matters of architecture and design, for a minister in Mandelson’s position to take. This was because the dome was to be the ultimate symbol of the triumph of New Labour. “If we can’t make this work,” the deputy prime minister, John Prescott, had said, “we’re not much of a government.” It was to be, said Tony Blair, “Britain’s opportunity to greet the world with a celebration that is so bold, so beautiful, so inspiring that it embodies at once the spirit of confidence and adventure in Britain and the spirit of the future in the world.”

It’s strange, now, to contemplate the passions it aroused. For millions of event-goers the structure is now the O2, where Harry Styles and Diana Ross are among the forthcoming attractions. The Millennium Experience that it contained then is dimly remembered, like a TV soap opera that didn’t catch on. It was eclipsed, as Blairite catastrophes go, by the invasion of Iraq three years later. In 2012 the London Olympics, many times more expensive but nonetheless perceived as a success, put the bad dream of the dome behind it.

For a bad dream it was. Advance publicity had been both negative and positive. It will be a monumental cock-up, had been one narrative; the Daily Telegraph columnist Boris Johnson had said he would eat his hat if it wasn’t a triumph. Then the opening night happened, 31 December 1999, which must go down as one of the greatest PR disasters in history. Thousands of VIPs, invited to celebrate this night of nights, this once-in-a-lifetime event, among them newspaper editors and the CEOs and chairs of sponsoring corporations, were made to queue for an hour or more for security checks, in the winter cold, at the tube station in Stratford, east London, from where they were to take the train to the dome.

Mike Davies, a director of the Richard Rogers Partnership, the architects of the structure, arrived with the Queen and some select others by boat. They found the place emptier than expected, he recalls, leaving them to make small talk with the monarch as guests “dribbled in”. (The architect Zaha Hadid, who refused to come unless by limousine, was also one of the earlier arrivals.) At about 2.30am the head of the British Airports Authority, says Davies, “grabbed me by the throat. He said: ‘You bastards, why didn’t you let us do the security? We know how to do it.’ His family had already stormed off. They were livid.” From then on, says Tim Pyne, a designer who worked on several displays inside the dome, “the press came down on the whole project, and us through association, like rabid dogs”. “Everything went right until the opening night,” says Michael Grade, the future BBC chairman who lent his expertise on showbusiness to the project, “and then the world turned against us.”

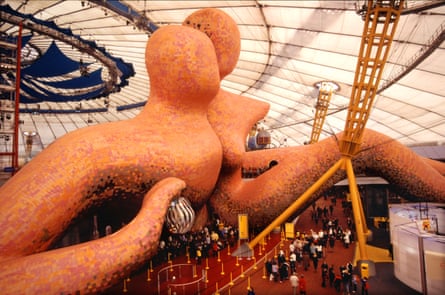

The contents were panned. They were described as underwhelming, compromised, communicating nothing in particular. The long queues to get into the star exhibits made front-page news. “Is this the arse or the elbow?” went a Private Eye speech bubble, coming from a visitor trying to enter an opening in the arm of a giant figure that was in a “zone” based on the human body. At the end of January, says Davies, “the merde hit the Vent-Axia”: ambitious targets for visitor numbers were not being met, which meant that revenue was less than hoped. “You could blow it up,” said columnist Boris Johnson later in the year, “… there must be some form of public humiliation. I’d like to see all those responsible for the contents of the dome eating humble pie.”

For a government famed for its supposed mastery of spin, it was about as bad a s it could get. It crystallised the doubts that floated around the New Labour project: this spectacular container of not very much made an easy emblem of the government’s preference for style over content, its attachment to vacuous statements of modernity, its use of messaging and focus groups to deliver meaningless platitudes, its tokenistic approach to regeneration. “I’m still haunted by the experience 20 years later, it was awful,” says Ben Evans, a member of Blair’s 1997 election campaign team who then worked on the dome’s content. Now director of the London design festival, he “came out of it thinking I was really unemployable”.

Like other works of New Labour, it was a modification of something inherited from the previous Conservative government. The project that would evolve into the dome had been enthusiastically backed by Michael Heseltine, deputy prime minister in John Major’s government. It had started with the Millennium Commission, set up under Major, which was charged with spending a portion of the funds generated by the new National Lottery on things that had something or other to do with the impending new millennium. “We had billions of pounds to spend,” says Simon Jenkins, journalist and a member of the commission, “and why? On a date.”

One idea was for some kind of festival to celebrate this momentous moment (although, as pedants never tired of pointing out, the third millennium would technically begin on 1 January 2001). “There was a general acceptance that it would happen,” says Jenkins, “although no one could think quite what it would be.” Bids were invited. The shortlist of locations consisted of Birmingham, Derby, Stratford and the Greenwich Peninsular, the latter the site of a former gasworks, its soil burdened with arsenic and mercury and unexploded bombs. It was the evil twin of the better-known version of Greenwich, the one with the lawns and old ships and baroque architecture.

Greenwich won, both because it offered the opportunity for renewal of a brownfield site, and because the line of the meridian, zero degrees longitude, runs through it. Here, it was claimed, was the place where the millennium would begin. (Again, a pedant speaks: the millennium actually started on Caroline Island, Kiribati, which is just to the east of a westward-pointing projection in the International Date Line.) The Millennium Commission would run the project until a new organisation, the New Millennium Experience Company, was set up. Jennie Page, formerly of English Heritage, was appointed chief executive, first of the commission and then of the NMEC. Gary Withers, founder of the design and branding company Imagination, was invited to help deliver the project. The Richard Rogers Partnership, already responsible for masterplanning the hoped-for redevelopment of the peninsular, was also asked to advise.

Still no one could decide what the festival was about, or what was in it. Withers, according to Mike Davies, gave a deadline of 25 March 1996 for the Commission to make up its mind. After this point he would be unable to produce the show, which was conceived as a series of pavilions in the open air, on time. The Commission didn’t make up its mind. Withers said he couldn’t do his job. It was then that Davies, along with his team at the Richard Rogers Partnership and the engineers BuroHappold, came up with the idea that became the dome – a great oversailing roof, in fact a tent rather than a dome, within which individual displays could be constructed. Protected from the weather, these could be simpler and quicker to build, more like stage sets than buildings. The structure that still stands was thus a clever way of buying time, a monument to the indecision of the Commission.

With Tony Blair’s election in 1997 came the danger that his predecessors’ project would be cancelled. Jenkins wrote an eloquent letter on its behalf, inviting Blair to imagine the joy of his young son Euan attending the event. The cabinet, many of them sceptical, discussed it. Prescott said his piece. It was given the go-ahead, on condition that the roof covering be upgraded such that what had until now been planned as a temporary construction could become permanent. Mandelson was made the minister in charge. It was an appealing detail that his grandfather, Herbert Morrison, had played the same role for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which for Jenkins and others was the main model for the proposed millennium event.

From now on, as Jenkins puts it, it would be “a showcase for New Labour, for Cool Britannia”. Blair had publicly aligned himself with a vision of Britain as a creative, dynamic country: food and furniture by Terence Conran, buildings by Richard Rogers, art by Damien Hirst, music by Oasis. The dome and its contents would be its expression. Major corporations would sponsor different elements – a process that had started under Heseltine. This would show, as Jenkins puts it, “that New Labour was friendly to capitalism, that business was part of one big national family”.

It would be, if it hadn’t been before, a political project, with potentially fatal consequences for true creativity. It would come with the legendary New Labour demand that everything should be on message, that interactions with the media be strictly controlled. “If you talk to the press,” one participant remembers being told, “we will destroy you and you will never work again.”

Still, though, nobody knew what it was all for, or about. If Page was an able administrator (“a genius,” says Jenkins, “a genius,” Grade concurs, “a very strong person,” says Davies), she was no visionary. There were calls for a creative director, what Jenkins calls an “impresario”, calls that were satisfied and then not satisfied by the appointment of Stephen Bayley, founding director of the Design Museum. After a difficult few months, his short-term contract was not renewed. He left a trail of eloquent barbs as he went. “Every sensible opportunity to make sense of the dome’s extravagant uselessness has been ignored,” he wrote in his book Labour Camp, “it is a pseudo-event.”

The hole in the dome’s heart, the place where a big idea should have been, became a void into which competing interests – political, commercial, cultural, individual – rushed in. The contents would be divided into 12 “zones” on different aspects of contemporary life – work, rest, the body, the mind etc – but it was still open what might be said about each. A “Litmus Group” of the great and the good was set up, to give feedback on ideas. “Does your name mean,” asked one intellectual contributor, “that you change from blue to pink depending on which party is in power?”

Page had the task of reconciling the unreconcilable, with results that were broadcast in The Dome: Trouble at the Big Top, a BBC Two documentary series produced at the time by Robert Thirkell and Adam Wishart. They paid particular attention to the faith zone, where the architect Eva Jiřičná wanted to create a spiritual space specific to no particular creed. Her ideas were mashed into a pulp by the Lambeth Group, a commission of clerics consulted by Page: Jiřičná’s early proposal for an asymmetric pyramid was felt to be too pagan, too new age; the Christians in the group complained that there should be more attention to the fact that the date in question, 2000, had something to do with the birth of Jesus. The end result, in one of many moments reminiscent of Spinal Tap’s micro-Stonehenge, included a curving plasterboard wall indented with crosses, each one carrying a TV screen in its centre.

The designer of one of the zones now recalls an attitude that was “so condescending”. Zaha Hadid, asked to shrink the mind zone that she was designing, was furious. “You can’t slice my work like a salami,” she said. Tim Pyne recalls the pressure from sponsors: his living island zone, on the theme of the environment, had the misfortune to be sited next to the transport-themed zone, sponsored by Ford, who “started to attack me for a negative story we were telling about car emissions”. They also demanded “that we remove an old VW Beetle, and a rusty Mini Cooper from the top of our recycled white cliff because they weren’t Fords. These were populist references to Herbie and The Italian Job; hardly controversial.” He tried to stand his ground. “The Beetle and the Mini were craned down, however, by the NMEC as an appeasement, and replaced with Vespas. Wimps.”

All the time there was the relentless pressure of the deadline of deadlines, 31 December 1999, the one that under no circumstances could be missed. Page’s achievement was to meet it, against considerable odds. But “in that drive,” as Ben Evans puts it, “anything that got in the way was swept aside”. He also wants to stress that, although the project’s £789m cost sounds large, the huge area of the dome meant that the “per metre spend was woefully inadequate”.

Small wonder, then, that most of those involved now describe the contents as “ultimately unsatisfactory”, as Evans puts it. Charles Falconer, the minister who took over responsibility for the dome after Mandelson resigned from government in December 1998, now says that “it didn’t succeed in its short-term goals. It was meant to be an inspirational exhibition that captured the imagination of the country at the turn of the millennium, and it didn’t do it.”

Most, though, want to say that the show that was eventually put on wasn’t all bad. The body zone, designed by Nigel Coates as a fusion of a male and a female figure, was memorable. Evans has a fond memory of the rest zone, a “zen-like space” in which he remembers “a coach-load of pensioners just lying against the wall, bathed in light. I thought: ‘fantastic, that’s worked’.” People speak fondly of what Grade calls the “pretty sensational” acrobatic performances, “the most dramatic flying that had ever been done indoors”. And 6.5 million people came, making it the most visited paying attraction in Britain. The trouble was that the unrealistic figure of 12 million had, against the advice of Jennie Page and others, been made the official target.

Most say that the dome itself, the structure of masts and its fabric covering, is what Falconer calls an “inspirational building”. Mike Davies emphasises its efficiency and economy: it cost £43m, which is not much for something covering 87,000 square metres; at less than 20kg per sq m, it is “the lightest building in the world. That’s magic stuff.”

Above all, say Falconer and others, the dome was vindicated by its “enduring and powerful legacy” – the still-ongoing building of homes and offices in “what was a deprived part of London”, the success of what Grade calls a “brilliant venue”, the O2 Arena. What actually happened was the 48-acre site that included the dome was sold to a consortium called Meridian Delta for a nominal sum, with an additional 86 acres of adjoining land thrown in, in return for a share of future profits on the site. At the time of the transaction it was promised that “up to £550m” would be returned to the public purse, and at least some of it has. Nick Shattock, a developer who was part of the Meridian Delta bid, says that “the government will get far more than that. I’m sure of that.” He says the dome shows how “events venues can be great drivers for residential and commercial development”.

Given that the site was boosted by additional hundreds of millions of public investment – the extension of the Jubilee line there, decontamination of the land adjoining the dome site – the staging of the Millennium Experience seems like a roundabout way to achieve a profitable private-sector entertainments complex plus a development that is still not complete. Falconer, though, argues that it “focused the resources of the state” on this difficult location. Regeneration there “could have happened without the dome, but it wouldn’t have happened without the dome”.

More generally, it is striking on how much those involved now agree – that the main problems were political interference, the lack of creative direction or clear statement of purpose, the unrealistic target for visitor numbers, the relentless timescale and deadline, the compromises that came with large amounts of corporate sponsorship.

My own aversion to the dome, at the time, came from its undermining of the hopes raised by the Blair government about both urban renewal and design. The talent arrayed there, which might have been put to use in the parts of cities where people actually live, was corralled into a compound. It was buried in a Thames-side bog with a plastic bag over its face. It set a pattern for the next decade of urban regeneration in which the power of iconic objects was overrated, in which bold-sounding political statements were then undermined by risk-averse delivery, in which the skills and integrity of architects and artists were crushed by the mechanics of public-private partnerships. In which partnerships the real power lay on the private side.

At the time that Blair’s cabinet gave the dome the go-ahead, it was spurred on by what Evans calls “the motivating factor of jealousy from other countries”. This was to be a rival, or more, to the grands projets that had appeared in Paris over the previous decade. Evans also believes that the Blair government was taken by surprise by the scale of their victory in 1997: “They didn’t quite see what they could do with their power.” Perhaps the dome might be seen as a sign of their insecurity, a manifestation of impostor syndrome.

Liza Fior, of muf architecture and art, whose proposal for an ice rink was binned early in the proceedings, argues that what would have been really impressive would have been to define British greatness in a different way. “Instead of making exhibitions of ideas” – for example, about investing in the local, or about the environment – “they could have really pursued those ideas.” Well, yes.